Participatory Development Explained - The Zahana Way

After almost a decade of work, wanted to take a step back, and reflect on the bigger picture. Participatory development is quite a mouth full of big words, 'rural transformation though participatory development' even more so, but what does it mean?

After almost a decade of work, wanted to take a step back, and reflect on the bigger picture. Participatory development is quite a mouth full of big words, 'rural transformation though participatory development' even more so, but what does it mean?

This reflection was inspired by watching the TEDx talk by David Damberger: What ahhpens when and NGO admits failure" We learned that many water systems built in Africa don't function much longer than one or two years, for reasons eloquently explained in this TED Talk link.

We encourage you to watch it. It is an outstanding 13-minutes critical analysis by an insider who has built many water systems over the years and has implemented the lessons learned in an innovative and inspiring way. Without mentioning it explicitly, he also presents a good case why GlobalGiving’s approach of matching donors with projects directly is better for both sides.

But now to the before mentioned bigger picture: Many of you remember that Zahana set out in 2005/6 on the adventure to build a clean, safe water system (and then two schools. Water links to the right take you to many pictures and in depth information.)

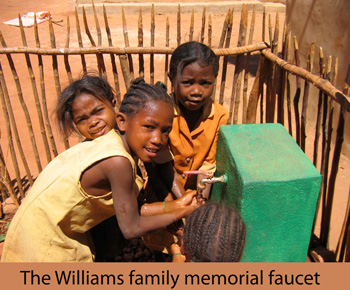

The water system was our very first participatory development effort. Still flowing uninterrupted for thirteen years now, it is providing clean water for over 1000 people. Way up in the mountains, some 2.5 km or 1.6 miles away from the village, a clean spring coming out off the ground is channeled with pipes into a water storage container on the mountainside. From there it flows, gravity fed through PVC pipes into the village. Collected in a second large water container at the edge of the village, the water flows into seven communal faucets that are accessible by all.

We built this water system by recruiting and hiring the water technicians (the people who actually build systems), and paying them to live for three months in the village. Living in the village community, far away from home, the technicians built the water system together with the villagers. This way, not only did they put in village sweat equity, digging trenches, cutting stones, carrying cement and sand, and laying pipe, that made the system more affordable; but they learned how their water system functioned. As an added benefit, the community was trained by the water technicians on how to fix the system, should it break one day. All systems built by humans are bound to break sooner or later, but now the villagers are not only prepared on what to do, but also hopefully have the skills to do it themselves without outside help. As an additional safeguard, one man, jokingly referred to as the ’water police’, has been assigned to walk up and down the water system every day, to check for leaks or potential problems. Besides the salaries for the water technicians, Zahana paid for materials the villagers could not afford, such as PVC pipes, the water storage containers and cement with your help.

We built this water system by recruiting and hiring the water technicians (the people who actually build systems), and paying them to live for three months in the village. Living in the village community, far away from home, the technicians built the water system together with the villagers. This way, not only did they put in village sweat equity, digging trenches, cutting stones, carrying cement and sand, and laying pipe, that made the system more affordable; but they learned how their water system functioned. As an added benefit, the community was trained by the water technicians on how to fix the system, should it break one day. All systems built by humans are bound to break sooner or later, but now the villagers are not only prepared on what to do, but also hopefully have the skills to do it themselves without outside help. As an additional safeguard, one man, jokingly referred to as the ’water police’, has been assigned to walk up and down the water system every day, to check for leaks or potential problems. Besides the salaries for the water technicians, Zahana paid for materials the villagers could not afford, such as PVC pipes, the water storage containers and cement with your help.

It is exactly the participatory element that made it so successful. Zahana worked with the villagers to build their water system together, instead of an outside organization coming in and building it for them, making it ‘their water system’, not ‘ours’. With this proud ownership of ‘their water system’, comes the responsibility to take care of it and maintain it. The fences built two years ago to protect the faucets are another indiactor. The only complaint being (that makes us quite proud in turn): people from Fiadanana don't like to drink the water in other places anymore, and are now forced to carry their own water with them, if they are leaving their village.

It wasn't easy to find water technicians willing to live in a rural setting for many weeks, and work with an untrained workforce, since this was and is quite a novel concept in its cultural context. But it paid off in more ways than one, because we were able to build the water system for less than 20% of water systems (normally) cost and it is still flowing strong for almost 6 years. Although, still the single biggest success for us is that no child has died of diarrhea since the clean water system was built.

It wasn't easy to find water technicians willing to live in a rural setting for many weeks, and work with an untrained workforce, since this was and is quite a novel concept in its cultural context. But it paid off in more ways than one, because we were able to build the water system for less than 20% of water systems (normally) cost and it is still flowing strong for almost 6 years. Although, still the single biggest success for us is that no child has died of diarrhea since the clean water system was built.

Participatory development means, and that is at the heart of it, to trust people that they will do their best, when you give them a chance to take charge for their own development. That is neither easy nor commonplace (not only) in the development community and requires a lot of work and dedication. And there will always be failures and mishaps along the way, as much as we all would like to avoid that. And: Yes, it does require outside money, too. In a country such as Madagascar where a farmer may “make” less than US$ 300 in a year growing rice with backbreaking manual labor, we will always need people like you supporting our efforts to make this participatory development possible.

Yes, everybody wants to know, including us, how do you measure success?

Well, get a glass of water (most likely it comes out of a tap of even a bottle for you), and take a good long look at this clean, crystal clear, safe drinking water, and think where it comes from - before you quench your thirst.